Curating art on a deserted island: Montecristo Project

Margherita Falqui

22 September 2020

A “world within a world” of contemporary art, far from the white cube.

There is a deserted island off the Sardinian coast, unreachable and mysterious, which seems to be inhabited only by prickly pears and granites, more of a mirage than reality: it is here that the transversal artistic-curatorial Montecristo Project, conceived by the two artists Alessandro Sau and Enrico Piras, is developed as the natural second phase of their previous project Occhio Riflesso, whose speculative paths, research and artistic experimentation continue, around themes such as the de-contextualisation of the work of art, display, documentation and evocative power of the image.

The complex nature of this project was best expressed by the artist Paolo Chiasera, who happily defined it as a "psycho-institution": a space that is first of all conceptual, and only later concrete. An opportunity for reflection, speculation, for overturning the fossil paradigms of the contemporary art world, a journey of artistic research that attempts, in the words of Montecristo's duo, to "shuffle the cards on the table, looking for new solutions to problems that are now urgent".

Following the principle that an artist recognizes, understands and takes care of another artist better than any other professional in the art world, in Montecristo project it is the artists themselves, Alessandro and Enrico, who produce, curate, set up, photograph, document and, last but not least, write: they organise exhibitions by inviting artists to the island, often underestimated, forgotten or emerging, and displaying their artworks in a space that is rethought and adapted to each new exhibition. The island and the exhibitions can only be visited by invited artists and are not accessible to the outside public, except through the filter of photographic documentation.

An essential aspect of the project is also theoretical speculation, radically carried out with great freedom and independence on the Montecristo writings blog. Given the value that the written word upholds within this complex and fascinating project, we wanted to interview Alessandro and Enrico, creating an opportunity to deepen and directly share some reflections and elaborations starting from the theoretical knots they face in their work.

Your latest project has addressed a constitutive element in Sardinian culture, the so-called “resisting constant”, that is the preservation of its own originality independently from external influences. In light of contemporary curatorial discussions, which often focus on themes such as colonialism, can we still talk about Sardinia as an artistic-cultural island, of a resisting island?

We strongly believe that it is still possible to speak of a “resisting constant” when referring to Sardinia’s artistic-visual production, provided that this identity resistance is sought in territories that can escape the classical artistic historicization.

Let’s try to clarify this aspect: the idea of “resisting constant” in visual art has been the subject of three exhibitions, recently organised by the MAN museum, in which this theme acted as an umbrella for the presentation of artistic researches in Sardinia from 1957 to 2017. Studying this project we have realised that a majority of the exhibited works was actually/in truth, an attempt to erase this identity matrix, which an anthropological factor, more than artistic.

Sardinian art, since the 50s, has almost always tried to adapt to those linguistic novelties that spread outside the island, generating a certain strange detachment for which, to a social-economic context anything but modern corresponded a super modern art, in line with the latest tendencies, being that action painting or the kinetic Op Art. The result was thus a series of signs lacking a real referent traceable to some socio-economic sub-layer present in our island.

We thus find ourselves in the antithesis of “resisting constant”, since the languages of modernity were not suitable for expressing an idea of Sardinian social (and even less linguistic) reality, they were not generated or metabolized by artists, but only borrowed. Taken in these terms, the question of colonization is not only a geographical issue, but also and above all, of chronological and linguistic mismatches between the island and the "overseas".

Our idea was to propose a reading that relates modern Sardinia to ancient Rome. There were then two distinct currents in terms of technique and content: Patrician art (official, sought after, imported from Greece and not native) and plebeian (deriving from Middle-Italic art, simpler, rough and spontaneous).

We believe that something similar is happening even today in Sardinia: there is an elevated, "official", intellectual and modern art, and a popular, crude, simpler and almost unwritable notion of art. It is above all in this rejected, "symptomal" dimension that, in our opinion, we need to seek the idea of resistance constant. The identity matrix can manifest itself as a conscious or unconscious form. An example of the first form are those kitsch productions such as the sculptures of giant bronzes in the roundabouts of the villages, the pseudo-nuragic artefacts, the carnival masks that raised as regional symbols in key rings or in living rooms, all that hence expresses a mythical and one-dimensional identity connotation.

The unconscious part is gonfigured in the productions of all those figures, often anonymous, who work as outsiders, cannot be classified as artists, craftsmen, or sculptors. This dimension of the unconscious, of Warburgian "survival" of the image still offers today the possibility of finding the typical traits of the "resisting constant": a barbaric, anthropological, anti-humanistic production that arises from the need to make, even before the awareness of thought.

Our research, through writings, photographic explorations and curatorial projects, tries to expose this dimension that represents the other side of visual production in Sardinia, which, not having a chronological or linguistic development, but living in the "eternal present" of archaism, has little relevance for Sardinian art historians.

We are intrigued by the choice to locate your project on an island, a sort of middle earth out of time and space. The choice of the island (not as an imposed exile) is interesting, with all that it entails: remoteness, loneliness, detachment, isolation, unreachability, secrecy and mysteriousness ... why then such a strong and particular choice? How does it fit into your artistic-curatorial project?

All of the concepts you have chosen to describe the island reflect the romantic connotation it possesses for us, especially if we consider it in the historical-artistic meaning of the islands' imagery. Our choice, however, does not only follow this romantic wave, but it was the culmination of a practical, theoretical and very rational research on a series of issues that concerned not only the work of art itself, but also aspects related to the exhibition context. Under this more technical and conceptual aspect we wanted to express a concept of absolute of the work and its exhibition. We thus decided to recreate the whole thing in an original way, giving the work of art (Salvatore Moro's sculptures in the case of the first exhibition) almost a world within a world; a possibility for the work to "be" in the most beautiful and authentic way possible, regardless of all those social, economic, historical frames without which, it seems, art can no longer exist. And so perhaps even this purpose, although carried out in a more rational than intuitive way, has something romantic about it.

You often refer to the island as a sacred space, protected by the secrecy of its location and inaccessibility but also by the artistic operations carried out on it. How do you relate to the sacredness of the place? Do you rediscover it or reconstruct it, in the light as well of the ancestral relation between Sardinians and the mystic? How do you relate with the ancient relationship between art, sacred and profane?

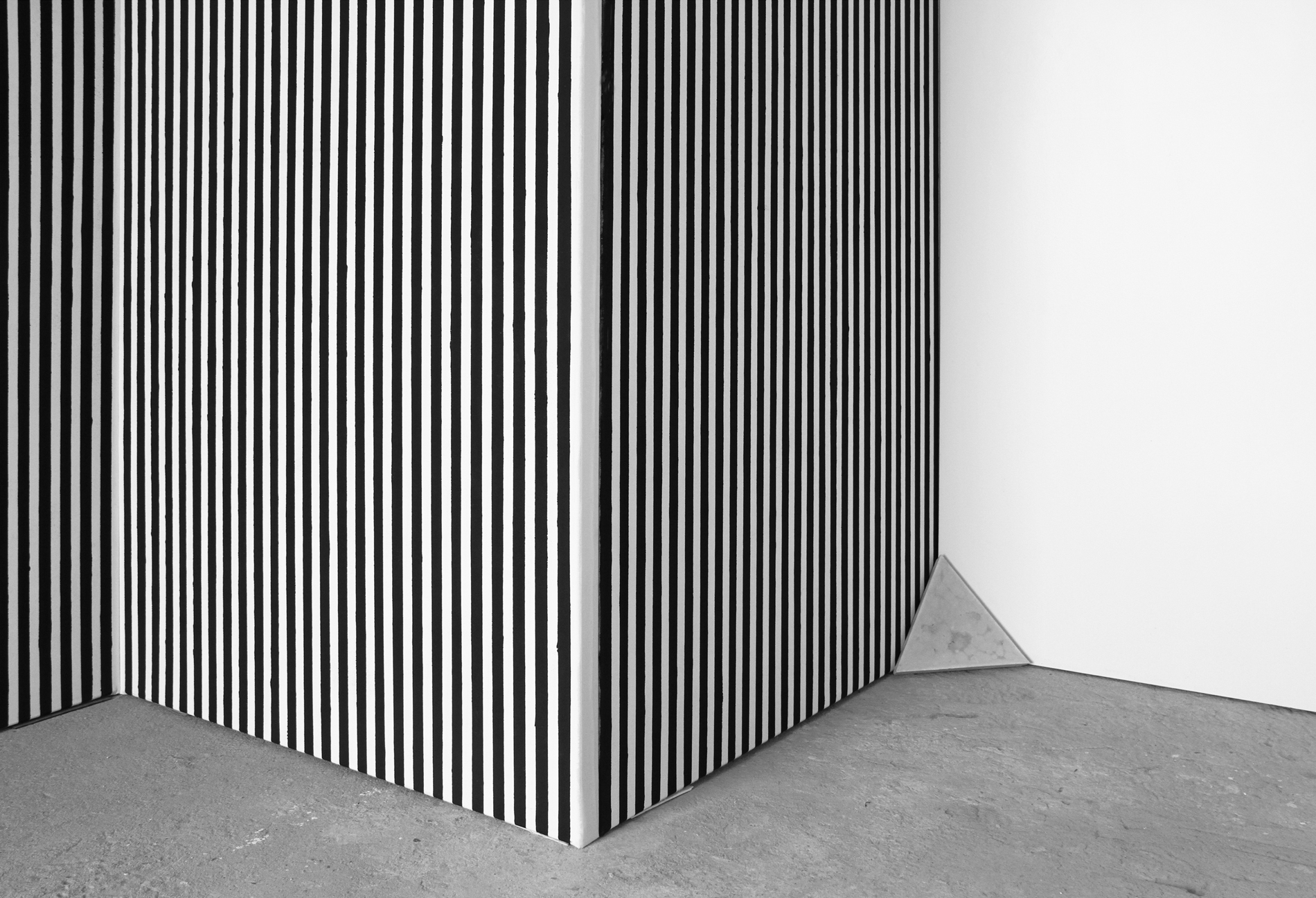

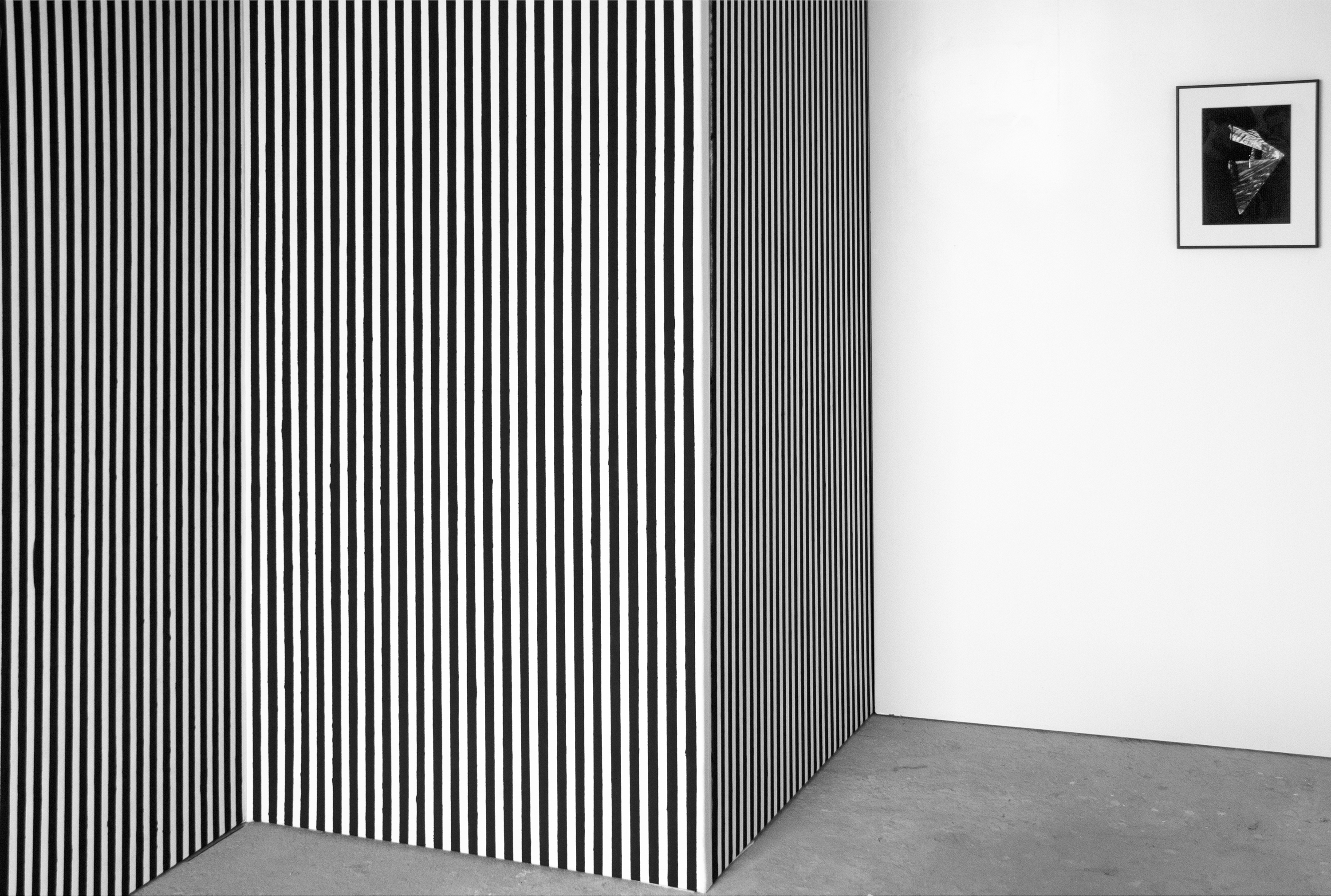

One primary thing that is important to clarify is the existence of the island. Many people think it is some kind of narrative ploy, a photographic fiction artfully built, but it is not so. To work in such a context means, first of all, to intervene in an "already given" with its connotations and complexity. The sacredness of natural space is clearly linked to its difficult accessibility: every sacred idea implies a form of distance and, geographically, mountains and islands give shape to this imaginary. Our interventions have been minimal and aimed at making the space accommodate works either in the natural environment, through plinths or natural cavities, or inside the tower existing on the island, which we have used as an exhibition space for the most fragile and perishable works.

The construction and reconstruction of the space constitutes our artistic work: the canvases, the plinths, the structures we create to house the works on display are also conceived as works, as is the photographic documentation. The material difficulty of working in this context constitutes its profane side and limits the possibility to realize more than one project every year. For this reason too we have created The "mountain department", an exhibition space in a secret location in the Sardinian mountains and dedicated to the artist and first director of the Galleria Comunale di Cagliari Ugo Ugo, with whom we have collaborated and to whom we have dedicated the project UU - The Artist as Director.

The de- and re-contextualisation of the work is recurrent in your work: you immerse and exhibit the works in a specific natural place. With the definition of "an aesthetic that is anything but natural" how do you interpret or decline the ancient relationship between art and nature? Granted that "it is the work that legitimises the space and not vice versa", is it within the relationship that you establish between a work and a specific territorial complexity that your making art manifests itself?

This question would require a small essay as an answer. Above all, it would be necessary to understand what we are referring to when we talk about the relationship between art and nature. History has left us with a load of immense information and problems, both in regards to the relationship between art and nature brought back to the concept of creativity, and on the relationship between art and nature translated into the notion of mimesis, i.e. the representative function of art itself. However, the point where our project comes closest is the relationship between subject and background, which is the most primordial sense of any representation. These elements of relationship with the natural world, both in terms of the organicity of the works with respect to a social or natural context, and in more purely photographic canons when we refer to the installation shot as the photographic dimension of the work, punctuate our path at various levels.

To answer the second question, it is certainly important to keep in mind the changing relationship in terms of legitimacy and assumption of value between these two apparently opposite poles: that they are the subject and the background, work and space, art and nature, art and museum institution etc. We cannot ignore the historical relativity with which the debate on art has been articulated over time. So today our making of art cannot only include the work of art, but must necessarily ask itself the question of its own legitimation of values with respect to the world.